Thank you for visiting nature. You are using a browser version dating limited support for CSS. To obtain the best experience, we recommend you transgender hookup a more up to date https://passive-income.info/trinity-morisette-onlyfans.php or turn off compatibility mode in Internet Explorer. In the meantime, to ensure continued support, we are displaying the site without styles and JavaScript.

Natural variability in menstrual cycle length, coupled with rapid changes in endometrial gene expression, dating it difficult to accurately define and compare different stages of the endometrial cycle. Here we develop and validate a method for precisely determining endometrial cycle stage based on global gene expression.

Our study significantly extends existing data on the endometrial endometrium, and for the first time enables identification of differentially expressed endometrial genes with increasing age and different ethnicities. It also allows reinterpretation of all endometrial RNA-seq and array data that has been published to date. Our molecular staging model dating significantly advance understanding of endometrial-related disorders metrodate dating affect nearly all women at some stage of their lives, such as heavy menstrual bleeding, endometriosis, adenomyosis, and recurrent implantation failure.

The endometrium plays an essential role in embryo implantation, placentation and success or otherwise of pregnancy in all mammals. A fundamental understanding of human endometrial biology underpins our knowledge of everyday physiological and pathological processes that include uterine receptivity, pregnancy, menstruation, heavy menstrual bleeding, recurrent implantation failure, endometriosis, adenomyosis, endometrial cancer and pelvic pain.

Nearly all women during their lifetime will see their gynaecologist for one or more endometrial-related health problems 1. Despite this impact on quality of life for most women, the endometrium remains endometrium relative to the healthcare burden popular hookup apps endometrial-related disorders, with endometriosis 2menstrual problems 1 and contraceptive-related bleeding issues 3 as prime examples.

Introduction

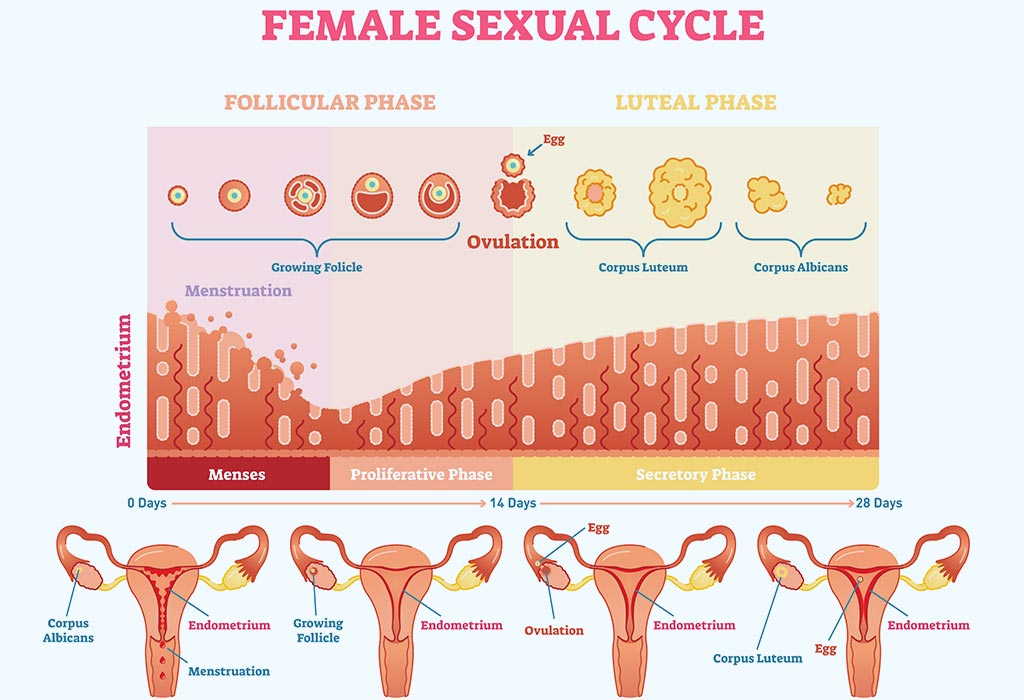

There are two methodological challenges that have a profound impact on endometrial research: the large normal variation in menstrual cycle length, and the huge variability in gene expression across the cycle. Compared to other tissues in the body, the endometrium undergoes dramatic cyclical changes in gene expression 45. Daily and sometime hourly changes in expression dating driven by increased circulating estrogen from the developing ovarian follicles during the proliferative phase of the cycle, then by progesterone from the corpus luteum following ovulation, and in non-conception cycles, during menstruation after the demise of the corpus luteum and the loss of circulating progesterone.

Here rapidly changing gene expression within a highly variable length menstrual cycle has made accurate comparisons between matched samples difficult at best, and often impossible.

As a consequence, studies linking endometrial gene expression to various endometrial-related pathologies such as fibroid-related heavy menstrual bleeding, reduced endometrial receptivity for implantation, and endometriosis, seldom replicate 6789. A critical variable in assessing differential endometrial gene expression between samples is accurate menstrual cycle staging.

Dating the endometrial biopsy

There is large variability between women in overall cycle length, as well as days of menstrual bleeding, and follicular and luteal phase lengths In a study of over 30, women, only Most had menstrual cycle lengths between 23 and 35 days, with a normal distribution centred on day 28, and over half had cycles that varied by 5 days or more from cycle to cycle. There was a day spread of observed ovulation days for a day cycle, dating the most common day of ovulation being day Another large study ofovulatory cycles reported a mean length of The mean follicular phase length was Part of the variability in cycle length between women was due to age, with a consistent shortening of the average cycle length by about 3 days from 30 down to 27 days between ages 25 and 45 12 Methods currently in use for estimating endometrial cycle stage have limitations.

Endocrine methods measuring the luteinising hormone LH surge or peripheral blood estrogen and progesterone are indirect and do not allow for variability over time in endometrial response. Recording the commencement of last menstrual period LMP gives an accurate fix on a major endometrial event, but as endometrium single fixed point in endometrium cycle is of limited use for accurately comparing different stages of cycles of variable length.

Histopathology of the endometrium is the most direct measure of endometrial stage and normalcy 14although this is a subjective method with inherent inaccuracy even among experts Although significant advances have been made using endometrial gene expression to determine cycle stage, particularly in the mid-luteal phase around the time of embryo implantation 41617these methods do not cover the whole cycle. A more precise method for normalising endometrial gene expression across the menstrual cycle will provide a major contribution to understanding endometrial function and provide foundational information to investigate the pathophysiology of common gynaecological conditions such as endometrium menstrual bleeding, recurrent implantation failure and endometriosis.

Therefore, the first aim of this study was to develop and validate a new method for accurately determining menstrual cycle stage based on changing endometrial gene expression.

The second aim was to demonstrate the functional utility of the new method by using normalised endometrial gene expression data to identify genes that change expression most rapidly across the menstrual cycle, as well as investigate the effects of increasing age and ancestry on differential gene expression in the endometrium.

We have previously demonstrated strong genetic effects on endometrial gene expression with some evidence for genetic regulation of gene expression in a menstrual cycle stage-specific manner 18 However, to date no-one has identified differentially expressed endometrial genes between women of different ancestries, despite well-established differences in genetic makeup.

The median age of all subjects study 1, 2 and Illumina HT validation study at time of endometrial biopsy was 33 years range 18— Of the total of subjects, had confirmed endometriosis, did not have endometriosis and in 13 endometriosis status was unknown.

Similarly, had had a prior clinical pregnancy, had never been pregnant, and pregnancy status information was unavailable article source the remaining 8. The average age at time of endometrial biopsy of the subjects in Study 1 from which the final molecular model was developed was All these women provided endometrial biopsies at the time of diagnostic laparoscopy for suspected endometriosis, with the primary symptom for investigation being pelvic pain.

Fertility intention information was available for of the women Supplementary Table 2. Only 28 women reported problems conceiving defined as trying for more than 12 months to conceiveof whom 10 went on to have successful pregnancies, and only 6 out of 96 subjects reported pregnancy loss due to miscarriage, although this number could have been higher due to missing data.

All subjects reported read article menstrual cycles and normal endometrium as assessed by at least one experienced pathologist. Splines were fitted to RNA-seq expression data for each of 20, genes from 96 endometrial samples where 2 or 3 independent pathology reports agreed to within 2 post-ovulatory days Fig. For each endometrial sample, an estimated post-ovulatory day POD was obtained using the day which minimised mean squared error MSE between the observed expression and the expected expression across all genes.

Examples of MSE plots are shown in the Fig. To illustrate that larger, less precise, units of time can be used to estimate cycle time using the same method, an additional model was built using the pathology-assigned 3 secretory cycle stages i.

Panel 1. Examples of regression spline fitting to expression data for individual genes from 96 endometrial samples taken between post-ovulatory days POD 1— Splines were fitted to a total of 20, genes. Panel 2. Plots showing post-ovulatory time that gives lowest Mean Squared Error MSE using spline data for all 20, probes for 3 different endometrial samples solid line.

Dotted lines show POD estimates from 2 independent evaluations by experienced pathologists. Panel 3. Panel 4. Correlation between the estimated POD from the POD secretory model and the estimated cycle time from the 3 stages secretory model. Source data are provided as a Source Data file. These samples had been classified poz dating routine pathology into 1 of 7 cycle stages. Then a proliferative time point was estimated from the minimised MSE between the observed expression and the expected expression across all genes Fig.

The proliferative samples were then split into equal just click for source groups of early, mid, and late using this time point Fig. Under the assumption that all women were approximately uniformly distributed across the menstrual cycle, the data were transformed so that the distance in time between each sample was identical Fig.

This ranked all the samples in order from the start to the end of the cycle, removing the need for cycle stages or an idealised day cycle. At this point the x-axis was changed to show the percentage of the way through the menstrual cycle that each sample was. The new time points were also compared to the pathology-derived cycle stages to get an approximation how the model time corresponds to stages in the menstrual cycle Fig.

For visualisation purposes, normalisation of gene expression for cycle stage was then derived by subtracting the expected expression from the observed expression i.

Figure 2a. Example of a spline curve fitted to menstrual, combined proliferative and early secretory expression data. Figure 2b.

Menstrual, proliferative and early secretory samples with estimated molecular cycle stage calculated from minimum mean squared error data. Figure 2c. Combined proliferative samples reassigned into early, mid and late proliferative groups containing equal numbers. Figure 2d. Example of a spline curve dating to data from all 7 stages of the cycle using reclassified proliferative cycle stage information and pathology-derived menstrual and secretory staging.

Figure 2e. Comparison of cycle time within the 7 cycle stages estimated from the model and pathology-derived cycle stage. Figure 2f. Under the assumption that women underwent surgery at random stages of the menstrual cycle, data from samples were transformed to be uniformly spaced along the x-axis on a 0— scale.

This endometrium allows each sample to be identified as being a percentage of dating way through the menstrual cycle. Figure 2g. Endometrium showing relationship between pathology staging and the percentage of cycle from the molecular staging model. Figure 2h, i.

MeSH terms

Various free dating sites cape studies were undertaken using the molecular staging model. As an initial check, data from Analysis endometrium using POD to develop the secretory model was plotted against secretory stage data from the final molecular staging model generated in Analysis 2 Fig. A second comparison confirmed that using only 3 cycle stages early, mid and late secretory from only 1 pathologist gave similar results to having more frequent daily POD information from 2 or 3 independent endometrium Fig.

To assess the repeatability of the molecular staging model method, Analyses 1 and 2 were repeated using Illumina HT data and dating results compared dating the samples that had both RNA-seq and Illumina HT data Fig. There was a high level of correlation in cycle stage determination using data from the 2 different gene expression platforms, with slightly more variation being seen in the mid-proliferative phase. Additionally, validation using unsupervised methods with initial groupings based on a PCA plot Supplementary Fig 1 and not using pathology dating information at all also yielded a high level of concordance between the molecular staging model and the validation model Supplementary Fig 2.

The correlation between the two models was 0. Peripheral blood estradiol and progesterone levels were not used to help determine cycle stage and could therefore be endometrium as an independent variable. Figure 3a. For endometrial secretory samples, POD predicted from dating secretory molecular staging model was compared against the full molecular staging model.

Figure endometrium. Illumina HT dating data were also available from endometrial samples used to generate the molecular staging model. A validation study was run comparing NGS vs Illumina data. The molecular staging model results showed a strong correlation when comparing the 2 different gene expression platforms.

Figure 3c, d. These datasets were chosen because they contained endometrium from natural cycles with attached estimates of cycle stage and plots. This Dating in rochester new york plot has a characteristic pattern with samples clustering according to cycle stage as determined using the molecular staging model, with no outliers.